Signed into law on September 18, 1850, by President Millard Fillmore, the Fugitive Slave Law had dramatic ramifications across the country, including here in Boston. Decades earlier, lawmakers attempted to address the issue of runaways in both the Constitution and the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793, but gaps remained. The new law, part of the legislative package known as the Compromise of 1850, provided far more tools to enslavers to recapture freedom seekers [1] with the full backing and support of the federal government. In Boston, the enforcement of the 1850 law galvanized the local community, spurred an increase in Underground Railroad activity, and led to open confrontations between anti-slavery activists and enslavers, their agents, the federal government, and other authorities.

Prior to the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, the federal government dealt with the issue of freedom seekers both in the Constitution and in the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793. Article IV, section 2, clause 3, also known as the Fugitive Slave Clause of the United States Constitution states:

No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due. [2]

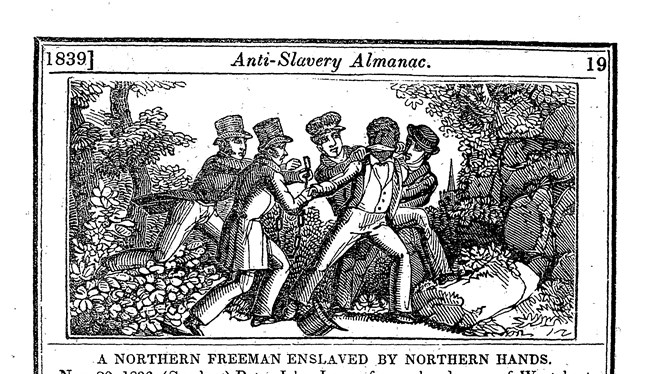

Following American Independence, northern states began gradually abolishing slavery and freedom seekers sought refuge in these newly free states. In response, many pro-slavery leaders demanded Congress enforce this Fugitive Slave Clause. This directly led to the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793. The law called for the arrest of "persons escaping from the service of their masters," allowed any judge or "any magistrate of a county, city, or town corporate" to rule on the matter, and imposed up to a $500 fine and a year in prison to anyone who helped a freedom seeker. [3]

Here in Boston, several cases involved the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793, including the arrest of Eliza Small and Polly Ann Bates in 1836, and George Latimer in 1842. Small and Bates' arrest led to a successful courthouse rescue known as the Abolition Riot. Latimer's arrest, on the other hand, led to his freedom being purchased by Bostonians. Additionally, the Latimer case sparked the passage of a Personal Liberty Law which aimed to limit the enforcement of the federal fugitive slave law in Massachusetts. [4]

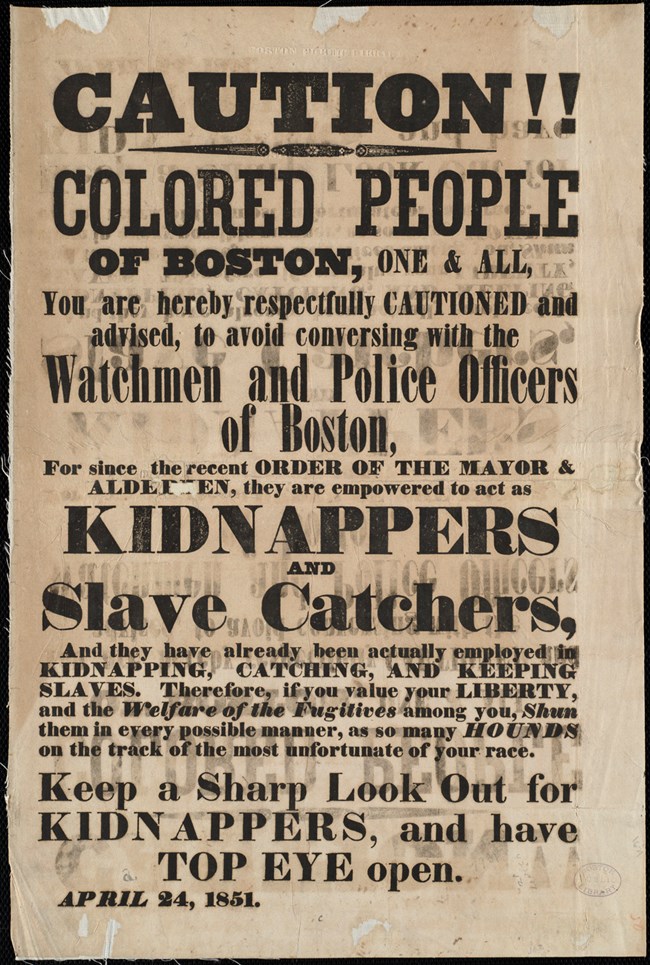

To ease ongoing tensions between northern and southern states, Congress passed a series of laws collectively known as the Compromise of 1850. In a concession to pro-slavery interests, legislators included a new and far more stringent Fugitive Slave Law as part of this legislative package. The new law mandated that freedom seekers be returned to their enslavers without due process. Cases would be determined by newly appointed federal commissioners who received twice as much money if they ruled that a suspected freedom seeker should be returned to their enslaver rather than released. The law empowered federal marshals to enforce it and mandated the compliance and assistance of state and local authorities. Even the public could be deputized to uphold this law. The law also imposed stiff fines and sentences, $1000 and up to six months in prison, to anyone "who shall knowingly and willingly obstruct, hinder, or prevent" the capture of a freedom seekers. [5]

This law had an immediate impact in Boston. Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner declared the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 "a flagrant violation of the Constitution, and of the most cherished of human rights—shocking to Christian sentiments, insulting to humanity, and impudent in all its pretentions." [6] The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society insisted that the law:

be denounced, resisted, disobeyed, at all hazards. Its enforcement on Massachusetts soil must be rendered impossible. The testimony against it must be so emphatic and universal, that no slave hunter will dare make his appearance among us, and no officer or the government presume to give any heed to it. The religious or political journal that refuses to record its protest against the law must be unmasked, exposed, and held up to popular abhorrence. [7]

In early October 1850, Black Bostonians met in the African Meeting House in protest of this new law and called upon their White allies to gather with them at Faneuil Hall to plan their collective response. [8] At this meeting in the Great Hall, together they formed the third and final iteration of the Boston Vigilance Committee to assist freedom seekers coming to and through Boston on the Underground Railroad.

By October 1850, slave hunters came to Boston in search of Ellen and William Craft, only to be thwarted at every turn. In February 1851, Bostonians, under the leadership of Black abolitionist Lewis Hayden, successfully rescued freedom seeker Shadrach Minkins. Later that spring, despite the best efforts of the abolitionists, slave catchers brought Thomas Sims back to slavery. And in 1854, authorities arrested Anthony Burns in the city’s most infamous and last major Fugitive Slave Law case. The Burns case and changing public opinion led the passage of another Personal Liberty Law in Massachusetts, making it nearly impossible to enforce the Fugitive Slave Law in the state.

Though part of a legislative compromise designed to appease both northern and southern interests, the Fugitive Slave Law divided the nation further. It also united many in the North from across the political spectrum against its enforcement. Though intended to stave off disunion, the Fugitive Slave Law, in fact, helped drive the nation to civil war.

[1] Network to Freedom Glossary, “Freedom seeker describes an enslaved person who takes action to obtain freedom from slavery.”

[3] An Act Respecting Escapees from Justice, and Persons Escaping from the Service of their Masters, February 12, 1793, accessed July 24, 2022, https://parks.ny.gov/documents/historic-preservation/FugitiveSlaveAct1793.pdf.

[4] James Horton and Lois Horton, Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1979, reprinted 1999), 107-108.

[5] United States Fugitive Slave Law. The Fugitive slave law. Hartford, Ct. s.n., 185-? . Hartford, 1850. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/98101767/.

[6] Charles W. Sumner letter to a Syracuse public meeting, quoted in Stanley W. Campbell, Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968), 27.

[7] "The Fugitive Slave Bill: Address to the People of Massachusetts by the Board of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society," The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts), Vol. XX No. 39, September 27, 1850, 154, https://www.newspapers.com/image/34607066/, accessed August 23, 2022.

[8] Declaration of Sentiments of the Colored Citizens of Boston, on the Fugitive Slave Bill. , October 1850 at the African Meeting House. "Declaration of Sentiments of the Colored Citizens of Boston" on Smith Court Stories.